Sustainabilities: Eco-oriented | Market-oriented

Richard Register first coined the term “eco-city” in his 1987 book Ecocity Berkeley, in the context of an organization called Urban Ecology. While there are no set criteria for what constitutes an eco-city, Register cites the significant influence of Paolo Soleri on the conception of the eco-city. Soleri, an Italian architect who designed his dream community, Arcosanti, in Arizona, described his fusion of architecture and ecology as “Arcology” (1969). After Urban Ecology, Register founded Ecocity Builders, which supports the development of eco-cities, which they define as “...an ecologically healthy city.”

-

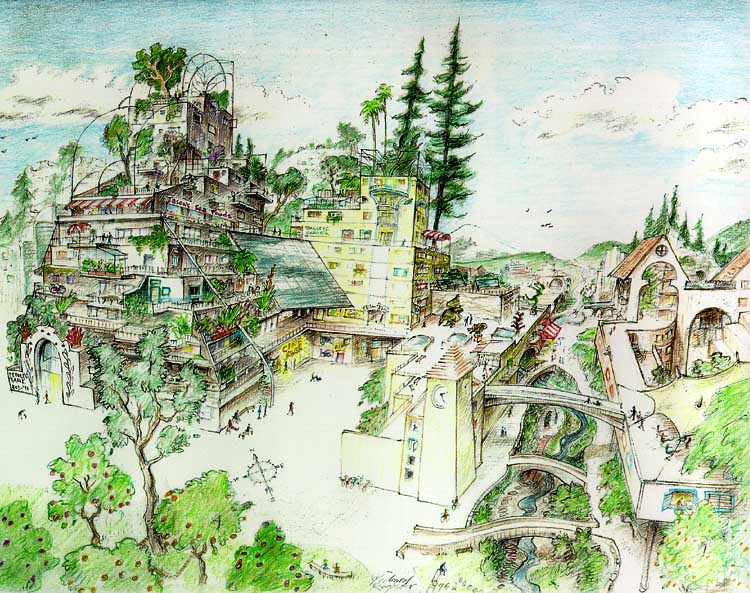

- Richard Register’s Ecocity Berkeley, circa 1987

-

- Keppel Corporation Eco-City, Singapore, 2008

Thus, the intellectual genealogy of the term eco-city originates from particular Bay Area, 1960s and ‘70s countercultural contexts. Ideologically, eco-cities signified ecologically oriented sustainability, combined with vernacular approaches to architecture and landscape design. The ideological roots of the eco-city have historically been anti-corporate and suspicious of science and technology, based on bottom-up, decentralized developments that seek to unite people and ecology.

The growth of the term and usage of “eco-city” has been relatively steady in the past three decades, but two distinct features have shaped changing eco-city discourse in the last ten years. In response to growing awareness of the problems of global climate change, eco-cities have increasingly become touted as a “solution” to environmental crisis. In addition, the concept of the eco-city has globalized. No longer a purely U.S. or Northern European phenomenon, high profile eco-city projects have been proposed and/or built in China, South Korea, South Africa, Singapore, India, and United Arab Emirates to name just a few locations. These projects have no common sustainability indicators, and many (although not all) share politically authoritarian governance structures.

What links them is a loose attachment to the “green” marketing of these projects, which are typically real estate developments. Here, the connection to the earlier generation of eco-cities is completely absent. In this global iteration, the term “eco-city” has been re-branded into a more market-oriented ideology (see Treasure Island as an example). Whereas the earlier focus of the eco-city was on community development, the current examples highlight the role of profit in sustainability projects. In addition, the earlier versions of the eco-city were relatively small scale and anti-hierachical. The contemporary global eco-city, however, is structured around hierarchy, with a tight interweaving of political and technocratic elites. Global engineering and architecture firms are key players in these new global eco-cities. The concept of the “eco-city” thus exemplifies how contemporary discourses of urban sustainability play a key role in framing, legitimizing, and accelerating dominant approaches to market-oriented urban growth.

— Julie Sze and Miriam Greenberg

Published June 1, 2015