Sustainabilities: Justice-oriented | Market-oriented | Vernacular

Sometimes referred to as the “Berlin Wall of San Francisco” because of the way the street currently divides the predominantly Latino and working class community of the Mission from the whiter and wealthier community of Bernal Heights, Cesar Chavez Street is seen by many as nothing but a polluted artery. What was once a thriving and walk-able business district before the freeway building movement of the 1950’s was turned into a grimy industrial road that today carries 50,000+ cars daily. Today, soot covered private and low-income public housing and the elementary school are sandwiched between large industrial buildings, gas stations, and a hospital. Speeding cars dominate this landscape, dissuading most people from using the sidewalks. Often, the only street life is day laborers waiting on street corners, hoping for jobs.

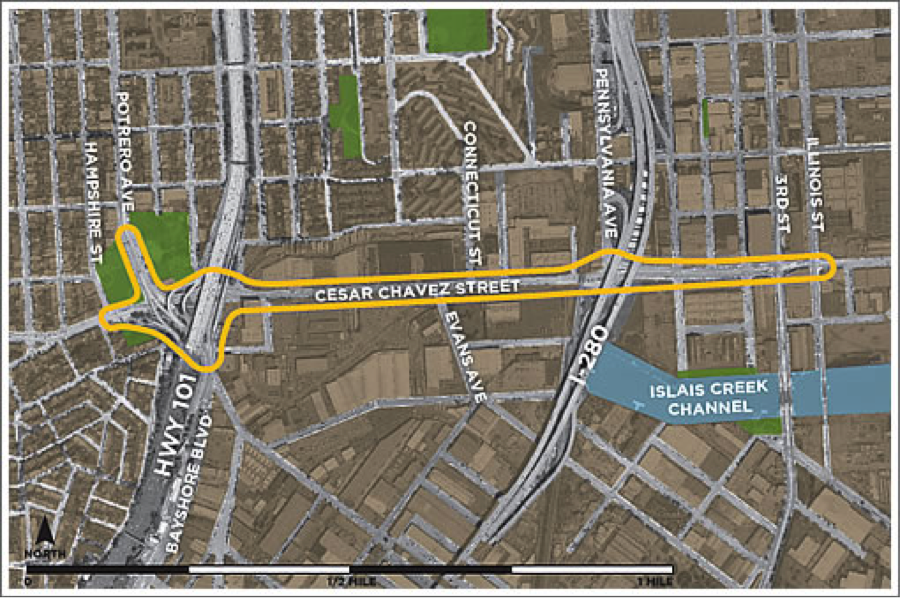

After years of community pressure and coalition building led by groups like CC Puede! (Cesar Chavez Yes We Can!) and The Bicycle Coalition, city departments have joined together to start a historic retrofit of the street, named the Cesar Chavez Streetscape Improvement Project. The new plan cuts two lanes of traffic and adds a tree-lined median strip, pedestrian bulbs, sustainable ground water collection, and bike lanes. Scheduled to begin in the summer of 2011 and be completed by Winter 2013, the remaking of this historic thoroughfare is going to change not just this one street, but possibly tear down the divisions between the neighboring communities.

As attractive as it is to push for Cesar Chavez to be redesigned as a more livable street, it is important to examine whether the solutions proposed will be long-term improvements that benefit the current surrounding community. Cesar Chavez Street is the southern border of The Mission District, a traditionally working class, partially industrial, neighborhood that has been fighting gentrification for decades, with declining results. While there were several successful fights against planned gentrification along the Mission transit corridor in the 1970s¹, in the mid-to-late '90s gentrification devastated the thriving Latino neighborhood. The dot-com boom of the late '90s brought an influx of money and new tech workers to the Bay Area, leading to the increase in rents and property that spurs displacement. The Mission District, a “mixed-use” neighborhood that had low property costs and proximity to several types of transit, was particularly vulnerable to the influx of money for redevelopment to provide housing and workplaces for the new, mostly white, high-income tech class. Former warehouses were turned into lofts, owner move in (OMI) evictions increased, and apartments were converted and sold as Tenancy-in-Common (TIC) condos. With the burst of the dot-com bubble, the displacement slowed, but continued.

Remarkably, the housing crash of 2009 and its ensuing recession and employment issues have done little to change gentrification’s steady progress through the area. According to the San Francisco Rent Board Report for 2009–10, the Mission District has the highest rate of OMI evictions in the city from 1994–2007. If anything, it seems that the crash has made more obvious the separation between the haves and have-nots, pushing those with little safety net out of the city in larger numbers than before, and opening the city to a more complete stage of gentrification, dominated by “creative class” workers for Google, Twitter, Facebook, and biotech companies such as Genentech. Like earlier waves of new residents, many of these Silicon Valley tech workers choose to live in the Mission because of its urban eclectic vibe, thriving restaurant and nightlife scene, quaint Victorian houses—but in addition, because of its proximity to the freeways, and to numerous stops on the corporate bus routes that connect them to their jobs in the Valley.

The southern portion of the Mission District bordered by Cesar Chavez Street, has historically been slower to gentrify than the northern portion, which is closer to downtown, SOMA, and the Castro. In addition, Mission Latino community institutions, such as The Mission Cultural Center, Galeria de la Raza, the Day Laborer Program (located on Cesar Chavez), Panaderia La Victoria—a 60-year-old business, and numerous churches are clustered in this area. Yet, is it possible that this new neighborhood amenity might contribute to a new phase of gentrification in this “final frontier” of the mission?

Certainly the new plan has many positive aspects that will aid current residents—and that current residents have long fought for. Beyond traffic calming and greening, these include added benefits like fixing flooding problems in the public housing and local neighborhood center, as well as creating safer access to the neighborhood public school. Unfortunately, it also seems to have left out crucial controls to maintain affordable housing and aid rent stabilization for current businesses or residents. Nor has factored in how the new plan will affect the day labor workers who congregate on the street, or the need to add more public transportation. Without addressing these concerns, it seems certain that a newer cleaner road will lead to increased property values, investment, and gentrification—potentially representing what some have called “environmental gentrification.”

Not so far away, in the Hayes Valley neighborhood, this exact chain of events occurred in 2007 when the Central Freeway was pulled down and replaced with the “livable” Octavia Boulevard². On Cesar Chavez Street, there are already new-build condos selling for over $1.5 million that use the street’s redesign as a selling point in their literature. “The location offers convenient commuter access and is scheduled for near future transformation by the Cesar Chavez Streetscape Improvement Project” says the realtor’s website.³

And so the question remains- Will this newest change help the area’s residents by cutting down on traffic, noise, and pollution, increasing pedestrian and bike safety, and making the neighborhood more sustainable and livable? Or will this be the last straw of gentrification in a neighborhood ravaged by the dot-com boom and market-led urbanization?

— Susie Smith

Published June 1, 2015

1. Mike Miller, “People Power In San Francisco: The Mission Coalition,” Race, Poverty, & the Environment 15:1 (2008), 65–67.

2. Robert Cervano, Junhee Kang and Kevin Shively, “From Elevated freeways to surface boulevards: neighborhood and housing price impacts in San Francisco,” Journal of Urbanism 2:1 (2009): 31–50.

3. Droubi Team Coldwell Banker “3119–3121 Harrison St” Accessed April 17, 2011 www.droubiteam.com

Visit Sites

- 16th & Mission

- Bateson State Office Building

- Bayview-Hunters Point

- Beach Flats Community Garden

- Cesar Chavez Street

- CicLAvia

- Ecotopia

- Fruitvale Transit Village

- Gonzales

- Googleplex

- Haight Ashbury Recycling Center

- Integral Urban House

- La Mesa Verde, San Jose

- Los Angeles Eco-Village

- Mandela MarketPlace

- North Berkeley Farmers’ Market

- Oakland Ecopolis

- Pajaro Valley Watershed

- Treasure Island

- West Oakland