Sustainabilities: Eco-oriented | Justice-oriented | Market-oriented | Utopian

“Oakland Ecopolis: A Plan for a Green Plan” was a manifesto formulated in the summer of 1997 for Jerry Brown’s Mayoral campaign of 1997-1998. It was written by Ernest J. Yanarella, Professor of Political Science and associate director of the “Center of Sustainable Cities” at the University of Kentucky, together with fellow academics Hugh Bartling, Robert Lancaster and Christopher Rice. Jerry Brown approached Yanarella to draft a sustainable city program that would form an anchoring platform for his mayoral campaign. Subtitled “Finding the Grassroots Resources for a Sustainable Vision for Oakland,” the document evokes a utopian vision, while also encompassing justice-oriented and ecological versions of sustainability. However, after reading it, Brown rejected the plan, citing its impractical aspirations for economic development.

Brown’s commissioning and disavowal of “Oakland Ecopolis” demonstrates his shift away from the ecotopian visions associated with his seventies-era ‘Governor Moonbeam’ persona and towards the pragmatic, neoliberal urban development approach he assumed as Mayor of Oakland—as epitomized in his "10k Plan" to bring 10,000 people to a newly developed downtown Oakland. The debacle of “Oakland Ecopolis,” in relation to Brown’s campaign promises and mayoral legacy, helps us to understand the unstable ideological role sustainability plays in shaping his approach to governance in California across his long career.

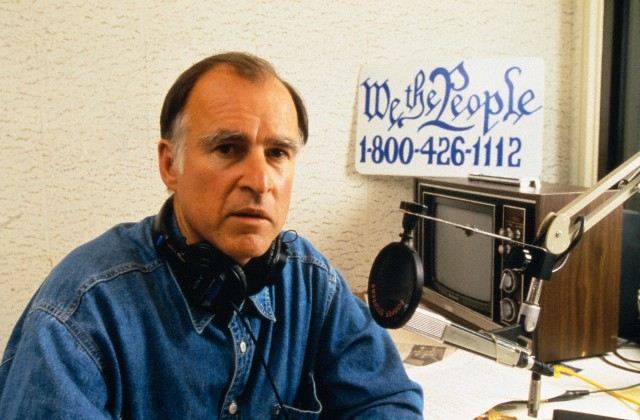

Jerry Brown hosting "We The People" on KPFA circa mid-1990s

A utopian manifesto, “Oakland Ecopolis” reflects a stronger version of the ‘sustainability tripod or the triple bottom-line’ that balances between economic, social and environmental well-being as promoted in market-oriented versions of sustainable development.¹ Yanarella et al attempt to combine imaginaries of Oakland’s strengths (i.e. its multiculturalism and Californian ecotopian ideas) with a brief outline of policies to create the plan for a sustainable urban vision of the city. It suggests a revamping of citizen participation processes along with green development as an economic driver for the city’s regeneration.

Replete with ecotopian imagery on the regeneration of the city through “the promise of a green future,” “Oakland Ecopolis” envisions a bleak urban landscape transformed into “a verdant garden mixing steel towers and tree-filled parks.” It lists pollutive car culture and excessive consumer culture as threats to ecological sustainability. Intertwining environmental and social sustainability, the manifesto proposes how the health of the environment and the Oakland’s civic life are mutually dependent. Through robust democratic citizen participation practices, Yanarella et al. call for citizens to “take back the design of their city” from “politicians, powerful interests and corporate fatcats who have eroded the public trust and sapped the common will.” There are also a few proposals for market-oriented sustainable development, which include the fostering of alternative energy sources and the transformation of one industry’s “negative externalities into the resources of another’s industry,” such that economic development “works within Nature’s economy and limits.” But Yanarella et al did not intend “Oakland Ecopolis” to be an actionable plan, and wanted it to become “catalysts for discussion in [Oakland’s] many [public] forums.”

The idealistic tone of the manifesto was consistent with Brown’s ‘Governor Moonbeam’ reputation, which grew from his involvement, during his earlier term as governor of California, with individuals such as provocateur Stewart Brand. Prior to the conception of “Oakland Ecopolis,” Brown advocated for ideas of proto-sustainability ideologically aligned with the communitarian and counter-cultural aspects of Whole Earth Catalog, which called for the general empowerment and improvement of the human condition. In the mid-nineties, he founded an educational non-profit We the People aimed at “strengthening democracy and the ability of people to shape the places where they live,” and conducted radio interviews with anarchist thinker Ivan Illich whom he considered a good friend; linguist, social critic and political activist Noam Chomsky; and avant-garde architect Paolo Soleri. In October 1997, after uploading “Oakland Ecopolis” to the We the People website, Brown catalyzed his mayoral campaign with the notion of Oakland as “an ecopolis of the future—a city that is both in harmony with the environment and in harmony with itself."

Yet this vision soon began to unravel. The plan and its authors were criticized in the San Francisco Chronicle, which linked “Oakland Ecopolis” unfavorably to Brown’s ‘Governor Moonbeam’ persona, and highlighted the lack of programmatic details in the plan. Within three weeks, possibly in reaction to these criticisms, and in keeping with his effort to cultivate a new persona as a political pragmatist, Brown dropped the plan and changed the tone of his campaign, falling in line with dominant ideologies of neoliberal urban development. He eventually disavowed the plan as “the academic meanderings of ‘two professors from Kentucky,’ and said, “I don’t talk about ‘sustainable development,’ I talk about downtown development.” This about-face was critiqued by Yanarella in the piece "How Green is Jerry Brown?"

From Ernest Yanarella's reflection on the failed "Oakland Ecopolis" plan. (Terrain.org: A Journal of the Built & Natural Environments, 2001.)

Brown decisively won the Oakland mayoral election in June 1998, collecting more votes than the ten other candidates combined. In his inauguration speech, there's no mention of Oakland Ecopolis. He instead pledged to "reduce crime, to bring 10,000 people to downtown to live, to...establish public charter schools...and to encourage artistic performance." A few months later, in a speech on sustainable development, where he expanded on the “10K Plan,” Brown alluded to the tensions between environmental efforts and the neoliberalization of politics: "When the G-7 nations get together...they talk about [reducing barriers to] opening up markets...That's the big picture on sustainability, and it's the reason why I don't like to use the word any more, because I think it's not very honest." Rather than sustainable development, Brown envisioned “elegant density” through the 10K Plan: "People are close to one another…there is culture and art, and yes, there is money and investment...I don't know how sustainable it is, but it is active."

Further, he argued, to attract private investment, municipal priorities would have to shift: "So we have to reduce crime. People aren't going to put up their good money if they feel they're going to get mugged...The city has to trump [the cleaner, cheaper, safer suburbs]." Brown makes no mention of low-income and Black residents, though the 10K Plan is racially coded. Alluding to the environmental ills of postwar suburbanization, coupled with the rhetoric of privatization and zero-tolerance policing, Brown's vision for urban life makes Oakland, then seen as a dangerous ghetto, palatable for white and white-collar workers. In addition, with its lack of attention to ongoing needs for affordable housing, the plan was derided by progressive and black leaders in Oakland as a form of "Jerryfication," and further, a form of political re-branding. Wilson Riles Jr., a former councilman who lost a bid to unseat Mr. Brown in 2002, argued Mr. Brown's entire mayoral campaign became a means “to change his image from Governor Moonbeam to ... someone who can get down and dirty and make change in a tough urban city,” and so to position himself once again for higher political office.²

The Uptown Apartments on Telegraph Ave., the LEED-certified centerpiece of Mayor Brown's 10K Plan.

Despite Brown’s change of heart and image, sustainability did end up as a featured element in the final plan, if of a different sort than in the Governor Moonbeam era. The Uptown Apartments, which opened in 2008 on a former brownfield site on Telegraph Ave, are among the first manifestations of the 10K plan, and became its symbolic centerpiece. With LEED certified architecture, low-flow toilets and move-in gifts of “green” coffee table books, The Uptown promotes sustainability as a greenwashed lifestyle choice, exemplifying market-oriented sustainability.³ Such development is a far cry from the ecotopian vision of “Oakland Ecopolis,”even while it capitalizes on and distorts the imaginaries of the manifesto’s ideas of vibrant urban life. Rather than “Oakland Ecopolis,” the 10K Plan, and luxury green buildings like Uptown, remain Brown’s enduring urban development legacy.

—Trisha Barua and May Ee Wong

Published May 12, 2018

- Ernest J. Yanarella and Richard Levine, The City as Fulcrum of Global Sustainability (New York: Anthem Press, 2011).

- Zusha Elinson, "As Mayor, Brown Remade Oakland's Downtown and Himself." New York Times, September 2, 2010.

- Forest City Developers, “The Uptown: Marketing Plan” (Oakland, CA, employee handbook, 2007), 127-168.

Visit Sites

- 16th & Mission

- Bateson State Office Building

- Bayview-Hunters Point

- Beach Flats Community Garden

- Cesar Chavez Street

- CicLAvia

- Ecotopia

- Fruitvale Transit Village

- Gonzales

- Googleplex

- Haight Ashbury Recycling Center

- Integral Urban House

- La Mesa Verde, San Jose

- Los Angeles Eco-Village

- Mandela MarketPlace

- North Berkeley Farmers’ Market

- Oakland Ecopolis

- Pajaro Valley Watershed

- Treasure Island

- West Oakland